Understanding the data

Denoting origin

Origin is defined in inscriptions in a number of different ways. The most common way of doing this is through the use of an ethnic adjective directly following the name of an individual, usually an adjectival form of a city (e.g. Barcinonensis to indicate an origin in Barcino), although sometimes ethnic adjectives refer to an origin within a particular community or peoples (e.g. Limicus to indicate an origin among the Limici). In some instances, however, it can be difficult to distinguish between ethnic adjectives and ethnically- or geographically-derived names, resulting in some ambiguity (on Roman onomastics, see Bruun and Edmundson 2015). Where potential ethnic adjectives appear where we would typically expect to find a Roman cognomen in an inscription, these are classed as onomastic designations of origin on the map; in the case of Marcus Licinius Veleiensis, for example, Veleienis is classed as a geographically-derived cognomen from the city of Veleia rather than a genuine ethnic adjective (HEpOnl 6677). Such a name may have been inherited, and a geographical link can be posited but not confirmed. There is also some ambiguity when people record origin by the term natio (e.g. natione Germanus), as it not always clear if this refers to a particular peoples or geographical region (see also Limitations of Mapping for the difficulty of mapping such examples). There are a number of other less common ways of denoting origin, details of which can be found in the Category Explanations. Thus while most designations of origin are straightforward both to interpret and to map, the ambiguities of some of the potential geographical data in inscriptions should be taken into account. It is also worth noting that the provision of an origin for an individual is not always linked to movement. In some cases, the origin of an individual is recorded even when they are commemorated in their hometown (see Table 1) or within the same region or province of origin (see Table 2).

The limitations of epigraphic data

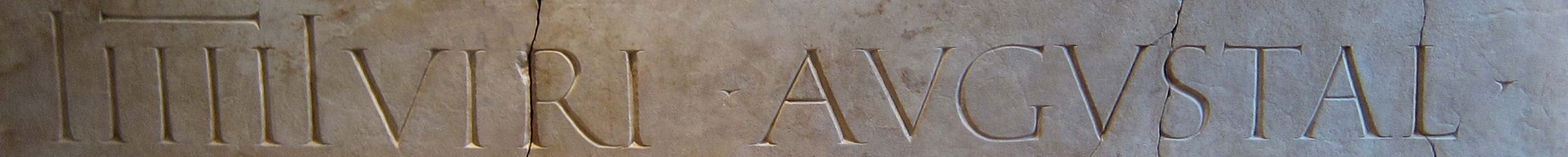

It is important to understand from the outset the limitations of the data that is displayed on the map. As this study of migration is based on inscriptions, the data is subject to what is commonly known as the ‘epigraphic habit’ (see, for example, Beltran Lloris 2015). Setting up an inscription to commemorate an individual’s life, a vow to a god, the construction of a building, or the setting up of an honorific statue represents a deliberate decision and is not a universal act, particularly when we consider that these are written in Latin rather than in any indigenous language of the region. Any study based on inscriptions is inevitably a study of a self-selecting group of people who choose –and crucially are able - to commission writing on stone; the wealthy, the military, and freed people are typically over-represented, while the poor and illiterate are typically under-represented. Moreover, recording an origin in inscriptions is not standard practice, and this study depends on individuals or their commemorators consciously choosing to identify their origins for specific personal or cultural reasons (see Denoting Origin for the different ways in which this is done). It is also difficult to distinguish between mobility and migration. Funerary monuments, for instance, simply tell us that a person died in a particular place; we do not know if they were there temporarily, whether this was a stop on a longer journey, or if they had migrated permanently to that location. It should also be noted that very few of the inscriptions can be dated with any precision, making it difficult to detect changing patterns in movement across time, or to link migration to any particular historical events. Inscriptions alone cannot then provide us with a full record of migration. It is suggestive of general trends rather than a definitive register of population movement.

The Limitations of Mapping

By necessity, journeys on the map are expressed as straight lines between the designated point of origin and the recorded findspot of the inscription (for details of how these points are mapped, see Building the Map). These journey lines are intended to be illustrative rather than a record of actual movement, particularly as neither the points of origin nor the findspots are always exact. Inscriptions were not necessarily found in situ as stones may have been moved and reused, and exact findspots are not always known, although movement of stones is unlikely to have been over distances significant enough to have any meaningful impact on the overall picture of population movement.

Furthermore, while most points of origin can be mapped accurately to a particular urban centre, those that are recorded as among a particular people, within a province, or from a town whose exact location is unknown, are mapped to a representative point and should only be taken as rough approximations of origin. One Fuscus, for example, is recorded as being of the Limici people and from the otherwise unknown location of Castellum Arcucis (HEpOnl 24349); his point of origin is mapped as a representative point within the territory of the Limici (Pl. 236519). Similarly, an enslaved person Albanus is described as natione Gallus, or of the people of Gallia (HEpOnl 14449); this can only be very roughly mapped to a representative point within the region of Gallia (Pl. 993).

When there is more than one location with the same name, the larger and better-documented city has typically been selected as the most likely point of origin, but this is always indicated in the accompanying commentary to an inscription. One Gaius Atilius Crassus, for example, gives his origin as Segontia (HEpOnl 9906). There are two locations known as Segontia in Tarraconensis (Pl. 246639; Pl. 246640), as well as Segontia Paramika (Pl. 236657) and Segontia Lanca (see Trismegistos, TM Geo 26979). The better documented city of Segontia (Siguenza: Pl. 246639) has been selected as the most likely point of origin, but this is clearly uncertain.

The distance between the point of origin and the findspot of the inscription is calculated in kilometres and given as the journey length, but this does not take into account the presence of mountain ranges, semi-desert regions, and the location of river crossings, bridges, or sea ports. In reality, the journeys undertaken by those moving must have been longer, significantly so in some cases; these real-life journeys will have reflected the layout of the road network, the course of navigable rivers, and coastal routes, and will typically have been undertaken by a combination of different modes of transport. Nor were they necessarily undertaken as a single journey.

Unmappable data

Although every attempt has been made to include all relevant inscriptions on the map, not all epigraphic examples of population movement could be mapped. Some points of origin could not be mapped, either because the locations are unknown or because there are several places with the same name (see Table 3), while others are fragmentary or unclear (see Table 4). One Gaius Iulius Reburrus (HEpOnl 9869), for example, records his origins in Segisama Brasaca, an unknown location (Pl. 241003), while in an epitaph found in Asturica Augusta, Marcus Persius Blaesus, a soldier with 26 years of service in the legion X Gemina, documents his origins in Hasta (domo Hasta: HEpOnl 14383). Pleiades records four places called Hasta, one in conventus Hispalensis in Spain (Pl. 256193), although over 600km away from the findspot, and three in Italy (Pl. 383670; Pl. 383669; Pl. 409224); it is not clear which Hasta is meant. In some instances, however, where there is more than one location with the same name, a decision was made to use the largest and best-documented city as the point of origin, but this is always noted in the commentary attached to an inscription (see The Limitations of Mapping for more detail).